A paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) a few days ago has made some impressive claims about a feature that, they suggest, is common to all languages. They’ve done a study looking at 37 different languages, measuring the average distance that dependent words in a sentence have between each other. The theory, Dependency Length Minimization (DLM), is that it’s better to have short dependence lengths because that makes language use more efficient and because it makes it easier to keep track of what the words in a sentence are all referring to. But first, we need to talk about claims of universalism. Let’s unpack this.

The first thing to do when anyone makes claims about a universal feature of language is to take a step back. Short of testing every language in the world for every kind of feature (an impossible feat, not least because languages are dying out at an alarming rate), claims of this kind necessarily need to use a subset of the world’s languages for their experimental data. So the first thing I looked at was the number and diversity of languages that this study used in their computations.

The number of languages was 37. Not bad considering they needed large collections of text from each language, already encoded in the required way. So for a comparative language study, I think this is a good number to start with.

The diversity of languages is ok, but it reveals where the usable texts are available and where they aren’t. I’d definitely prefer languages from further afield. My breakdown of languages by their language families looks like this:

- Indo-European:

- Romance: French, Italian, Spanish, Latin, Portuguese, Catalan, Romanian

- Germanic: Danish, English, German, Dutch, Swedish

- Greek: Ancient Greek, Modern Greek

- Indo-Aryan: Bengali, Hindi

- Indo-Iranian: Persian

- Balto-Slavic: Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Russian, Slovak, Slovenian

- Celtic: Irish

- Uralic: Hungarian, Estonian, Finnish

- Afro-Asiatic: Arabic, Hebrew,

- Isolate: Basque

- Austronesian: Indonesian

- Japonic: Japanese

- Sino-Tibetan: Chinese

- Koreanic: Korean

- Turkic: Turkish

- Dravidian: Tamil, Telugu

As you can see, the majority of languages are Indo-European, but as this is one of the biggest language families worldwide it’s not so surprising. Those languages are also the languages of some of the most wealthy and developed countries in the world, so again it’s not surprising that they are the ones with language data that can be used (and that we tend to focus on). There is a spread within the Indo-Europeans though, although it is very heavily skewed towards the languages of Europe. What about the hundreds of Indo-European languages in and around the Indian subcontinent? Also, I wonder how much additional diversity the very closely related languages provide? French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish; Swedish and Danish; English and German. Because they are so similar, it’s no surprise that they act the same way, which is what the data finds.

That brings us to the actual topic of the research. Dependency Length Minimization is a nifty idea about human cognition and how languages are suited to our human capacities (not surprising, given that we made the languages). It says that it’s easier to understand a sentence if the words that rely on each other (the dependent words) are closer together. The example from the paper is: John threw out the old trash sitting in the kitchen vs John threw the old trash sitting in the kitchen out. Both grammatically correct, but most people will prefer the first sentence over the second one, because its dependency length is smaller.

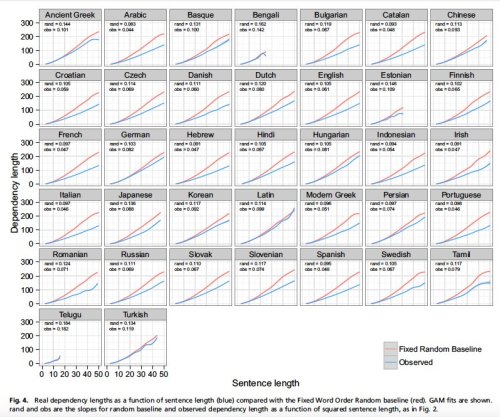

Going through huge collections of text from newspapers, blogs and novels, the authors found that the languages all displayed DLM to some degree. The amount of DLM in a language is affected by the word order of the language, the strictness with which that word order is considered important and other elements of the particular language. The authors suggest that since this is remarkably consistent across the languages they looked at, this might be something that is consistent for all other languages as well, to a certain extent. From a theoretical point of view it makes sense, and now empirically the evidence is pointing that way, even if there’s more to be done. But beware! More often that not, claims in linguistics of universals end up being disproven!

The question that still remains, and which the authors point out in the paper, is whether this is really an inherent feature of the language or if it’s a consequence of human cognition as we speak. Does the language demand this when we use it, or do we do this when we use the language? That’s an extremely tricky question to answer, verging on the philosophy of language. In any case, I found these findings fascinating. There are so many elements in how our languages work, and finding new ones is always fun.

“Does the language demand this when we use it, or do we do this when we use the language?”

I would strongly argue in favour of the second. Languages don’t exist independently of humans, so they cannot demand anything of us, in any meaningful way. They only exist as long as there are people to use them. Languages have the properties they do because those properties suit the articulatory, perceptual and cognitive needs of humans. What’s really remarkable is how many different ways these needs can be satisfied.

LikeLike

I think so too, mostly. I think that rigid grammars can, in a way, ‘demand’ particular behaviours of the speakers, but at the root, it is the speakers who control how they communicate. Completely agree on the remarkable nature of language diversity!

LikeLike